Is hydrogen the future for Australian energy?

Anyone watching the Federal Budget would have seen Treasurer Josh Frydenberg deliver a “high-spending, Australia’s bouncing back” budget with some big-ticket items aimed to drive the country out of its pandemic doldrums. To be honest, there weren’t any real surprises in this budget; it appealed to all. But many pundits agree that the budget missed out on one critical element: a clear carbon reduction and renewable energy plan for the country.

“What about hydrogen, you say?”

The Government said it’s forking out $1.2 billion towards emission reduction technology with carbon offset schemes and four “clean” hydrogen export hubs. Isn’t hydrogen the cleanest, most abundant source of energy known to man, with water as the only by-product?

Well…yes, but no. Let me explain.

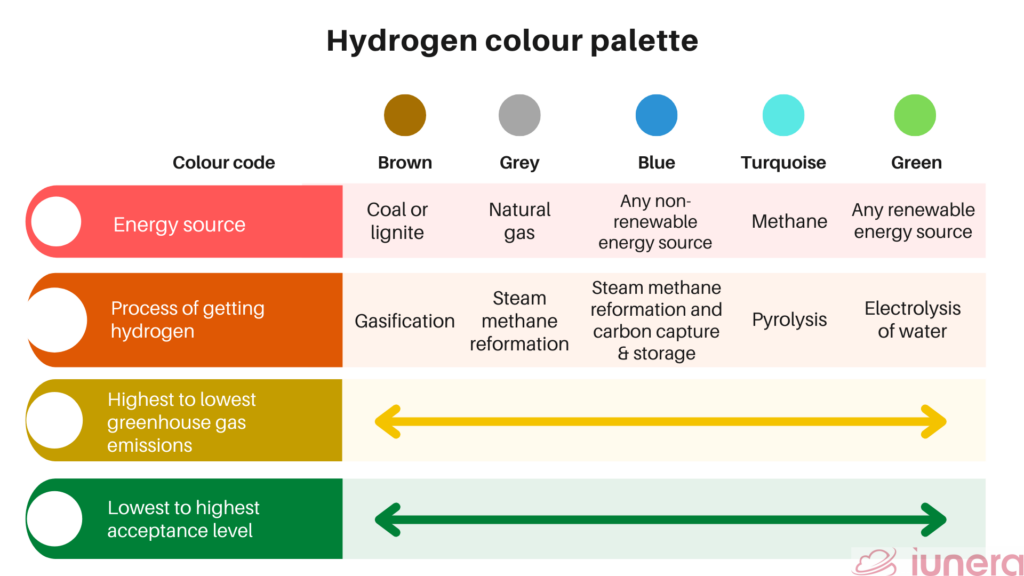

Following Joe Biden’s push for the USA to decarbonise, some experts say the days of coal, oil and natural gas are numbered. But are they? For those that don’t know, hydrogen is an abundant fuel that emits no carbon. It can be burned as a combustible fuel, or it can generate electricity in a fuel cell. But the problem is, hydrogen does not exist as a stand-alone element. It’s found with either oxygen (water) or carbon (hydrocarbons – coal, natural gas, oil). Hydrogen must be separated. It’s done in four ways:

- Brown Hydrogen – Made from coal with high levels of carbon emitted into atmosphere. High in carbon dioxide emissions.

- Grey Hydrogen – Made from natural gas with carbon emitted into atmosphere. High in carbon dioxide emissions.

- Blue Hydrogen – Made from gas with carbon captured and stored underground. Low in carbon dioxide emissions. .

- Green Carbon – electrolysis of water powered by renewable energy – No carbon dioxide emissions from this process.

In last week’s budget, there is no mention of the words “green hydrogen”. Instead, the phrase “clean” energy has been used. But how “clean” is clean? The government’s reference to “clean” is referring to a combination of hydrogen made from gas using renewable energy. The term is rather misleading; this is anything but clean in terms of carbon dioxide emissions. Carbon capture and storage (CCS) processes only entrench the use of coal, oil and gas. Both the United States and the European Union have signed off on multi-trillion-dollar economic recovery plans that, on paper at least, embrace real clean energy.

According to findings published in the Australian Renewable Energy Race report, the Climate Council found that “Australia is the sunniest country in the world and one of the windiest. Australia’s potential for renewable energy generation is 500 times greater than current power generation capacity.” Elon Musk has highlighted the fact that Australia has so much barren land that receives more sunlight than anywhere else in the world. According to the Climate Council, “Australia has more than enough renewable energy resources to power all our electricity needs,” yet despite having world-class renewable energy resources, particularly in wind and solar, “Australia has a low share of renewable electricity generation – seventh-lowest among 28 member countries of the International Energy Agency” (Australian Energy Regulator 2012). To some, this could be a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to get it right. Plenty of people believe that the benefits of renewable energy cannot be ignored; others argue that renewables have inherent flaws.

Is there a future in Green Hydrogen?

The Clean Energy Council (CEC) agrees that it is a positive step in the right direction for the “Australian government to pursue hydrogen as an alternative fuel source, but funds should be targeted at green hydrogen ‘hubs’ rather than blue hydrogen production, which generates CO2 emissions, albeit simply captured and stored.” Some jurisdictions in Europe and Asia have gone “all in” on their push for green hydrogen technology. Robert Hebner, director of the Center for Electromechanics at the University of Texas at Austin, summed it all up one sentence, “In Europe there was absolutely no doubt that it would have to be ‘green’ hydrogen. ‘Blue’ hydrogen would never do.”

And perhaps it may be the case that Australia simply cannot shift to renewables at the flick of a switch. Our energy production is heavily dependent on coal (75%) and gas (16%). The truth of the matter is, ‘green’ hydrogen is expensive, difficult to transport, it makes metal brittle and it is highly explosive. It may take years before ‘green’ hydrogen is cheap and easy to transport. According to an article by ABC, “Conventional hydrogen and blue hydrogen cost about $2 per kilogram, while green hydrogen is around twice as much.” That price is falling rapidly as it gets cheaper to manufacture the electrolysers required for electrolysis. An Australian National University (ANU) report found that “Australia could currently produce green hydrogen at about $3.18-3.80 per kg and at $2 per kg by the end of the decade.” At $2 per kg, it would on some analyses be cost-competitive with fossil fuels. In the meantime, Australia could start to “transition” by stepping through from ‘grey’ to ‘blue’ to ‘green’ hydrogen gradually. Energy Minister Angus Taylor is on the same page, saying: “This is about blending hydrogen into our gas network, so the purpose of this is to actually bring the carbon emissions of our gas network down.”

What is Australia doing?

According to an article in the ABC, one of the largest Green Hydrogen projects underway is the “$51 billion Asian Renewable Energy Hub, which plans to produce 26 gigawatts of cheap solar and wind power for the Pilbara. That’s more power than Australia’s entire fleet of coal-fired power stations.” The beauty of this, is that the renewable energy generated will go to electrolyse water to create hydrogen, which will be converted into ammonia for export. The process is completely carbon-free (apart from the emissions that resulted from the mining, smelting, transportation and construction of the machinery). Other developments include Origin Energy’s ‘green’ liquid hydrogen export project in Townsville, Engie Renewables’ 10-megawatt electrolyser project to produce hydrogen in Karratha, ATCO’s 10-megawatt electrolyser at its Clean Energy Innovation Park and Australian Gas Network’s 10-megawatt electrolyser at Murray Valley Hydrogen Park, in Wodonga Victoria.

Fortescue Metals Group (ASX: FMG), yes, the iron ore miner, has also been trialing a method where it turns iron ore into so-called “green steel” using “green hydrogen.” FMG says “one is electrolysis of iron ore, the other is using green hydrogen to reduce the iron ore all without coal.” While these processes are yet to be proven on a commercial scale, FMG is very confident; and if it is a private company that invests to prove-up and commercialise this technology, that’s great; it is a matter for its shareholders only.

Oil and gas players considered likely to boost gas infrastructure development are BHP Group (ASX: BHP), Origin Energy (ASX: ORG), Ampol (ASX: ALD) and Oil Search Limited (ASX: OSH).

The government can’t pretend anymore that the world is not changing. While a zero-carbon Australia might be a herculean (if not actually impossible) task, a gradual transition to hydrogen might be the best substitute for fossil-fuels in some areas, for example, making steel. As a nation, we sit at bottom ranking when it comes to spending on emissions reduction schemes, which some analyses contend create jobs and strengthen our economy. According to the Climate Institute, “it is estimated that nearly 32,000 renewable energy jobs (including over 6,800 new permanent jobs) could be created in Australia by 2030 with strong and consistent climate policies.” If that argument were to stack up in practice, it would make sense to go all-in on hydrogen.

We’re entering unchartered waters. A clear and combined ‘green’ hydrogen policy is arguably needed so that we don’t miss out scores of new jobs and positive economic development, and so that we don’t risk having our carbon-enriched exports sent back. Inaction may be felt a lot sooner than we think.